Postdoc fellowship – Governance and Local Sustainable Development

11/04/2024

2nd Global Urban Governance and Policy Conference – Call for papers

30/04/2024Conversation #62

Gender and local political leadership

by Adam Gendźwiłł

University of Warsaw, Poland

The underrepresentation of women among elected officials in national governments is a well-known fact. It is observed also among local authorities. The situation changes along with the social modernization in some societies – but rather slowly. This disparity has been investigated and targeted with different interventions, such as gender quotas or media campaigns encouraging female aspirants to run for office, not only to achieve higher shares of female decision-makers but also higher policy responsiveness to gender-based interests (so-called substantive representation).

When it comes to the descriptive representation (presence of women among elected officials), a common wisdom states that local governments provide a more inclusive place for women and politically disadvantaged groups, perfect to serve as a “steppingstone” in political careers. The share of women among local councillors varies from 11 percent in Turkey to 49% in Iceland, and among MPs – from 14 percent in Cyprus to 48 percent in Iceland.

Nonetheless, the data regularly published by the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) does not confirm the “pyramid” pattern of representation – according to which women would be more frequently elected at the lower tiers of multi-level political systems. The differences in the shares of women among local councillors and MPs are rather low. Among 38 European countries, in 20 cases the share of female councillors is actually lower than the share of female MPs, sometimes considerably lower. For example, in Germany 23.8% of councillors are female which compares with 35.3% of MPs (11.5 percentage points difference) whilst in Austria the difference is even greater (14.5 pp).

There are several potential explanations of this persisting ambivalent pattern, which are worth considering. Typically, most of the local councillors come from smaller municipalities, and much less from the largest cities. Local communities, particularly smaller, rural and more peripheral communities, frequently preserve traditional views on gender roles. Also, the process of elite turnover is considerably slower there. In many countries, these municipalities have also higher shares of men among local citizens, due to internal migration patterns. When (together with Kristof Styevers and Ulrik Kjaer) we surveyed electoral systems used in local elections across Europe, we noticed that various majoritarian rules, typically less favourable for women, were used more frequently in local elections than at the national level.

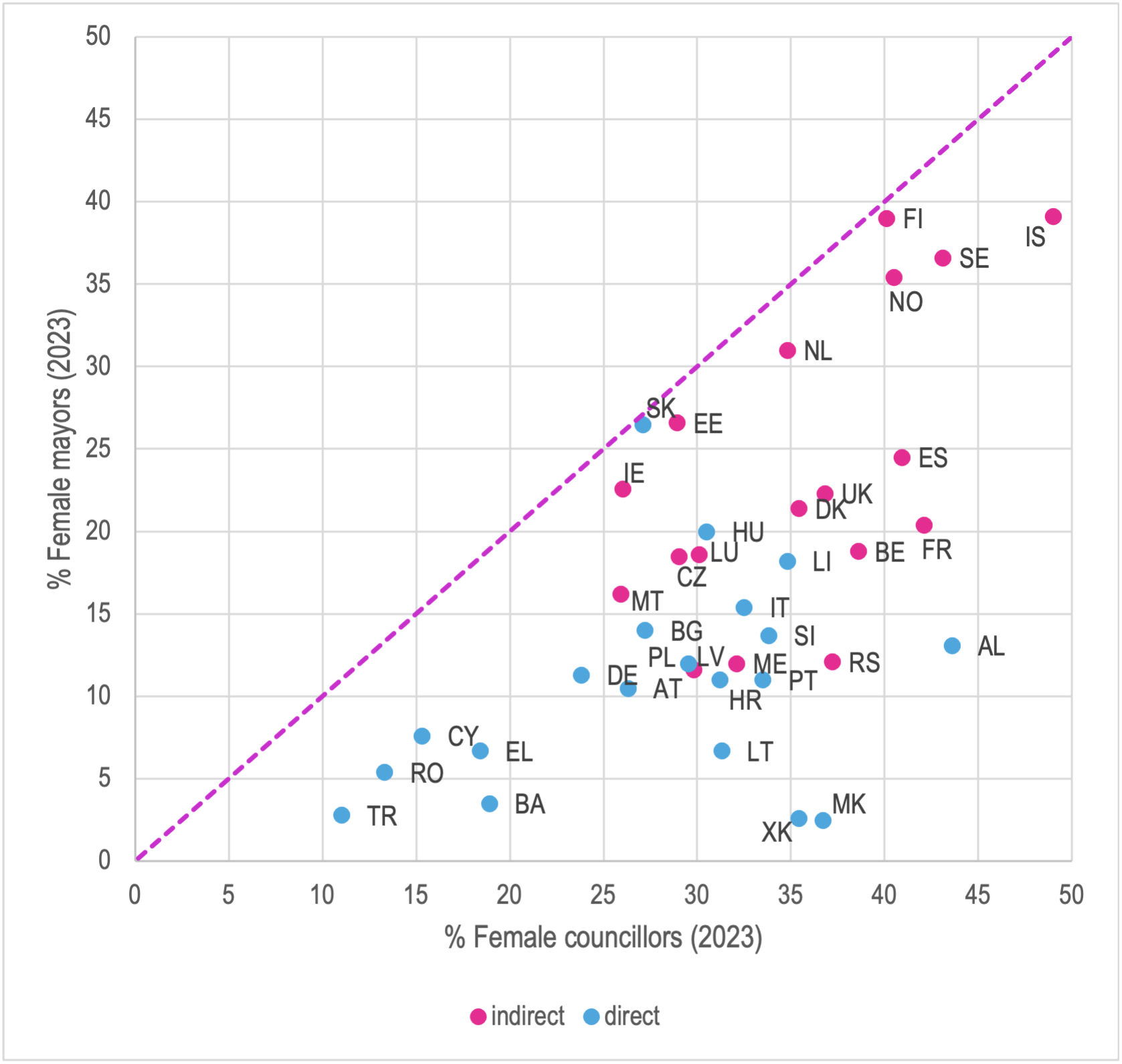

The overall picture is even more distant from parity, once we consider who wins local executive office – mayors or alder(wo)men. According to the EIGE data, in 2023 there was no single country in Europe where the share of women among mayors was higher than the share of women among local councillors, with Slovakia, Estonia and Finland being the closest to the equal shares and Albania, North Macedonia or Kosovo – the farthest (see figure below). This is an important insight, as under the “strong mayor” systems, mayors – not councillors – have a decisive role in shaping local policies. There is a clear discrepancy between countries in which mayors are elected directly and countries in which local executives are elected by the councils – the latter group having higher shares of politically active women and being closer to the equal shares of women among local officeholders.

Do these shares matter only symbolically? Inclusion of different socio-demographic categories is an important normative postulate to assure not only the legitimacy of representative democracy, but – even more importantly – the quality of deliberation. In the research on substantive political representation, the main assumption is that women may “bring to the table” different issues and prioritise different policy areas compared to their male counterparts, focusing more on welfare policies, social inclusion, and gender equality. The extant empirical evidence concerning local policy outcomes brings mixed conclusions in this respect. It refers both to the evidence based on surveys of policy preferences, and more sophisticated empirical studies based on various official policy indicators. Some of these studies have been systematically summarized by Hessami and da Fonseca; they argue that increases in female descriptive representation lead to a better provision of public goods in developing countries, while in developed countries the differences in spending patterns are not systematic. It seems that in the well-established political systems differences between parties matter more than the decision-makers individual traits.

Women among local councillors (X axis) and mayors (Y axis) in European countries

AL - Albania, AT - Austria, BA - Bosnia and Herzegovina, BE - Belgium, CZ - Czech Republic, BG - Bulgaria, CY - Cyprus, DE - Germany, DK - Denmark, EE - Estonia, EL - Greece, ES - Spain, FI - Finland, FR - France, HR - Croatia, HU - Hungary, IE - Ireland, IS - Iceland, IT - Italy, LI - Liechtenstein, LT - Lithuania, LU - Luxembourg, LV - Latvia, ME - Montenegro, MK - North Macedonia, MT - Malta, NL - The Netherlands, NO - Norway, PL - Poland, PT - Portugal, RO - Romania, RS - Serbia, SE - Sweden, SI - Slovenia, SK - Slovakia, TR - Turkey, UK - United Kingdom, XK – Kosovo

Still, many surveys of local politicians indicate that women and men in office frequently have different policy preferences. For example, Slegten and Heyndels identified that female politicians tend to support more leftist policies, and a gender gap in this respect exists also within parties. Slegten, Geys, and Heyndels investigating the preferences of Flemish local councillors found that women preferred increasing public revenues, while men preferred lowering expenditures. More generally – women in public office appear to be less eager to take risks related to debt than men.

Recently, together with Julita Łukomska, we found a similar pattern in a survey of Polish local councillors: male councillors were more in favour of increasing the local debt to avoid cuts in the investment plans. However, when we asked about the cuts in current spending, with local culture and education versus local roads maintenance as alternatives, councillors of both sexes preferred the latter option. Thus, the stereotypical gender division of views between different policy areas does not always re-appear in councillors’ policy preferences.

It is clear that we need more empirical evidence on the efficiency of various instruments promoting gender equality in the political domain at the local level, most proximate to the citizens, but also a better recognition of the values and interests brought by women to local political processes. In many instances, such as participatory or deliberative innovations, local government has proved to be an excellent arena for experimentation. Here, then, is another opportunity for local leadership and innovation.

References:

Gendźwiłł, Adam, Ulrik Kjaer, and Kristof Steyvers, eds. 2022. The Routledge Handbook of Local Elections and Voting in Europe. Abingdon: Routledge.

Gulczyński, Michał. 2023. “Migration and Skewed Subnational Sex Ratios among Young Adults.” Population and Development Review 49(3): 681–706.

Hessami, Zohal, and Mariana Lopes da Fonseca. 2020. “Female Political Representation and Substantive Effects on Policies: A Literature Review.” European Journal of Political Economy 63: 101896.

Slegten, Caroline, Benny Geys, and Bruno Heyndels. 2019. “Sex Differences in Budgetary Preferences among Flemish Local Politicians.” Acta Politica 54(4): 540–63.

Slegten, Caroline, and Bruno Heyndels. 2020. “Within-Party Sex Gaps in Expenditure Preferences among Flemish Local Politicians.” Politics & Gender 16(3): 768–91.

Acknowledgment:

Research on female political representation in local governments is supported by the Polish National Science Centre (grant no 2021/43/B/HS5/01059).

I welcome Adam’s intriguing analysis of the under representation of women in both local and national politics. If we take a long view, we can note that, in many countries, the role of women in political representation has grown during the last century. For example, in the UK, it was not until 1928 that women received the right to vote on the same terms as men. Fast forward to 2022 and we find that 36% of the 19,212 elected local councillors in the UK were women, a figure that compares well with 35% for the House of Commons. This suggests that progress has been made, but the figures also indicate that political representation in the UK is still nowhere near gender parity.

If we turn specifically to local government, a question that continues to challenge scholars relates to the interplay between the institutional design of local government and the resulting gender balance of local political leadership. Put simply: does institutional design help or hinder gender parity? During the last twenty years or so many countries – including Germany, Hungary, Italy, and Poland – have opted for the directly elected mayor form of local government on the grounds that this model can deliver high profile, accountable and decisive political leadership. There is solid evidence to support this claim.

But the evidence also suggests that there could be a ‘gender downside’ to this model of local governance. Comparatively few directly elected mayors are women. The direct election of an individual person can promote a ‘presidential’ approach to local leadership, and this emphasis on the individual leader may put some women off seeking electoral office. It is also the case that there are other more ‘collective’ approaches to local leadership as seen, for example, in several Scandinavian countries and it may be that these are more attractive to women. Perhaps ongoing research on gender and representation can, then, prompt fresh thinking about how we design local government institutions. Can we design institutions which deliver place-based leadership that is both strong and inclusive?

With increasing importance of local and regional governance questions related to the descriptive representation of the sexes are becoming more prevalent. Such questions are typically formulated in relation to numbers. Hence, we tend to look at proportions of women in relation to men. But what do these numbers really mean. Countries like Iceland, Bolivia and Tunisia have roughly the same proportion of female local councillors, can we assume that these countries have the same level of gender equality? If we do not agree with that, what does that tell us about descriptive and substantive representation or more precisely how do we translate quantity into quality?

As both Adam and Robin point out, institutional design matters. How we design our electoral procedures and leadership appointments matters when it comes to hindering or advancing gender equality, but how it matters and in which combination is not always clear. In effect gender is a social construct, therefore we cannot always translate research findings on gender issues found in a specific setting onto another context.

Consequently, success stories like the Icelandic story are not easily transferable to other settings. One of the reasons is that we do not fully understand how we reached that success. This means new research territories as we must understand how do we keep up the good work and prevent backsliding when it comes to gender equality at the local level.

Adam Gendźwiłł’s stimulating essay has underlined fundamental and perplexing trends in women’s representation across European local governments. Despite various interventions aimed at increasing the number of female politicians, such as gender quotas and advocacy campaigns, progress remains slow and uneven, illustrating a complex interplay between cultural norms and political structures.

The persistence of traditional gender roles in smaller and rather peripheral rural municipalities seems to significantly contribute to this disparity. Gendźwiłł highlights the slower elite turnover in these areas, which might be reinforced by majoritarian electoral systems that are less conducive to female candidates. This contrasts with the optimistic assumption that local governments serve as accessible stepping stones for political careers for women.

The ethics of gender representation is equally important as the question of whether equal representation makes a difference. Although opinion surveys of mayors and councillors organized by Hubert Heinelt’s team indicate that female representatives have differing opinions and views, especially on the notions of democracy, conducting an empirical analysis of policy outcomes remains challenging. Exploring the potential of local governments as sites for participatory and deliberative democratic innovations could provide valuable lessons on fostering more inclusive governance structures.